When on a date with my now wife during the weeks before we got engaged, we were taking a walk on the boardwalk by the sea. It was early spring and the partly warm and partly cool sea breeze at the beginning of nightfall was pleasant as we strolled along the promenade. The sound of the waves was soothing and gentle as I walked with the woman who was to become my wife and the mother of my children. Our relationship, by this time, had already developed to the point where not talking could be as comfortable as talking. We spoke intermittently, enjoying the feel of the breeze, enjoying the sound of the waves and just enjoying each other’s presence.

Suddenly the peaceful enchantment of our seaside stroll was abruptly interrupted by the shouts and insults towards us by a disheveled, drunk, perhaps also drugged, looking man who sat on a bench not so far from us. He looked as though he’d soon be approaching middle age, though his condition made it a bit hard to tell. He was unbathed and unkempt. While his insults were unpleasant, we didn’t really find them hurtful in light of his state of mind and state of body. It seemed more annoying than anything else. My soon to be fiancee then said something to me that, besides confirming my inkling that this was the woman whom I wanted to be the mother of my children, would actually change my perspective as a father and as a person. This is what she said, “It’s so sad. Just think about the hopes and dreams that this man’s mother must have had for him when he was a baby.” “Yes,” I thought to myself, “Just think about those (vanished) hopes and dreams.” The feelings of annoyance quickly shifted to pity and sorrow, and then to a deep sense of regret at the profound loss of potential that we were witnessing before our eyes. What had the mother of this man imagined for him when he was young? A happy life. A productive life. Probably marriage and a family, and perhaps so much more. And there he was, destitute and inebriated and lost. Indeed, it was so very sad.

Every human life holds so much potential, but what can we do to bring it out? How can that potential be actualized? That encounter on the boardwalk planted the seed for me for what has become some of my most central and driving questions as a parent:

What can I do to guarantee, to the very best of my ability, that such a thing will not happen to my children and to all the children whom I am able to influence?

What do I truly want for my children and what can I do to promote that vision?

What should I stop doing that’s interfering with my children’s own happiness and healthy development?

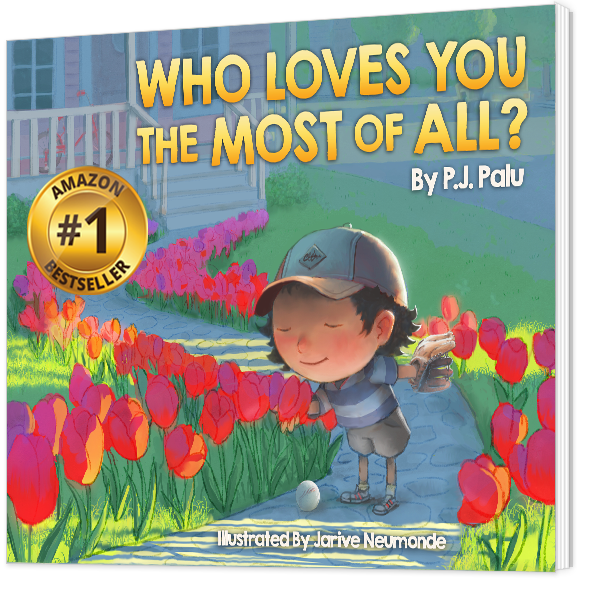

Who Loves You the Most of All? became the first step towards my answers to these questions.